Income gaps between states have stopped narrowing at the same time that rising housing costs—linked to increased zoning restrictions—have reshaped who can afford to live in high-wage places.

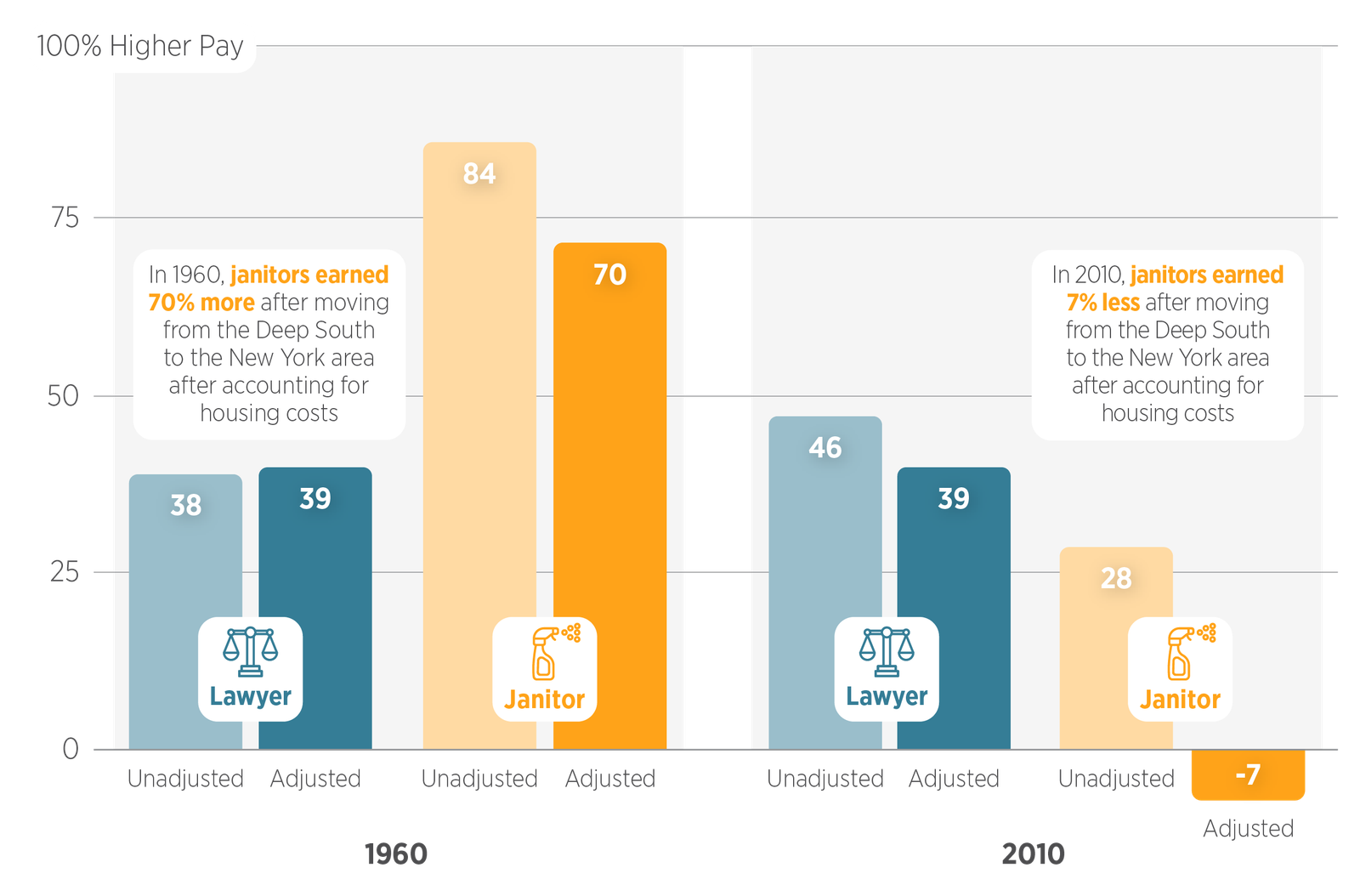

Is it worth living in a major labor market, where wages are higher, but so is rent? For much of the 20th century, the answer was yes. Higher wages generally offset the higher cost of living. Today, however, it depends.

High-income states begin to peel away, climbing sharply, while many lower-income states flatten out. Because of this divergence, income gaps across states have persisted and in some cases widened, despite the century of convergence that came before.

For high-earning college graduates, the wage premium often justifies the expense, while for low-income workers without a college degree, skyrocketing housing prices wash out the gains. This divergence carries profound implications for our economy, culture, and politics, and in this paper, the authors document these trends and model the forces that may underlie them.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of state per-capita income from 1880 to 2010, adjusted for inflation. For the first hundred years of this period, the lines steadily pulled closer together: poorer states rose toward richer ones, and by about 1980 the gaps had narrowed substantially. This was the era of regional income convergence, when workers moved from low-income states to high-income states and migration helped balance wages across the country.

After 1980 the pattern changes. High-income states begin to peel away, climbing sharply, while many lower-income states flatten out. Because of this divergence, income gaps across states have persisted and in some cases widened, despite the century of convergence that came before.

Figure 2: State Income Over Time

The slowdown in convergence reflects a parallel slowdown in migration. Flows of workers from poorer to richer states, once a powerful force equalizing incomes across regions, weakened sharply after 1980. As a result, the cross-state balancing of labor supply that used to narrow income gaps has diminished. Increasingly, whether and where workers move depends on their level of education.

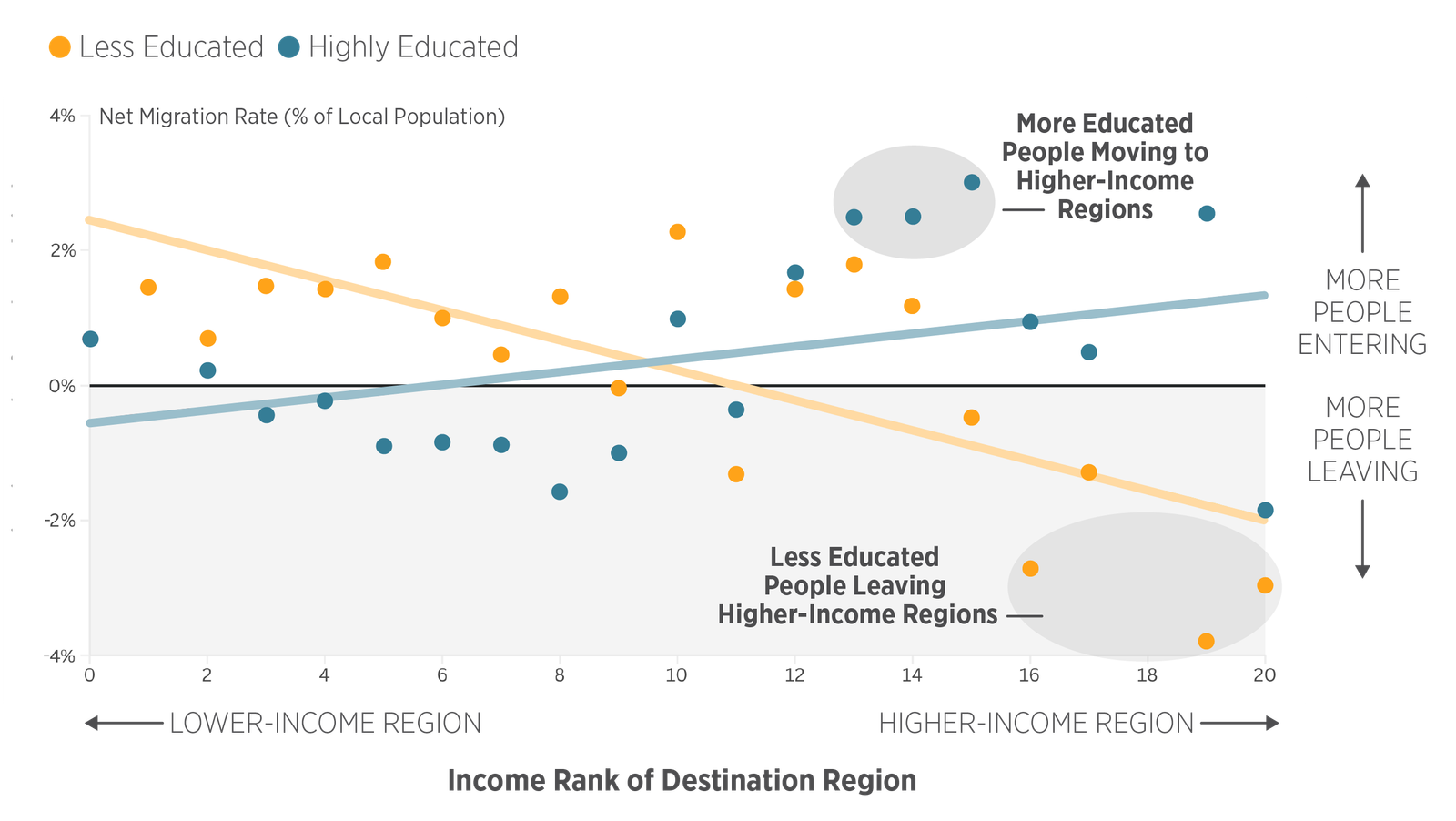

The slowdown in convergence has not affected all workers equally. Using census data, the authors show that migration patterns have diverged by education level. In the mid-20th century, workers with and without college degrees tended to move from low-income to high-income states. Today, that pattern holds primarily for workers with degrees. Those without, by contrast, are now more likely to move away from high-income places.

Figure 3: Net Migration Flows by Skill Group, 1995-2000

Figure 3 illustrates this pattern: net migration rates for college graduates (blue) still tilt upward with income rank, while rates for those without a degree (yellow) now slope downward — indicating net out-migration from high-income areas.

As a result, net migration flows no longer redistribute human capital across regions as they once did. This phenomenon, which the authors term skill sorting, marks a sharp departure from historical trends and may help explain the weakening of regional income convergence. Instead of low- and high-wage workers flocking to the same thriving labor markets, there are now places that attract college-educated workers, and others that retain or receive primarily workers without degrees.

Figure 4: Housing Costs and Supply Constraints

Select a tab below to explore more. Hover over or click on a point to view the data.

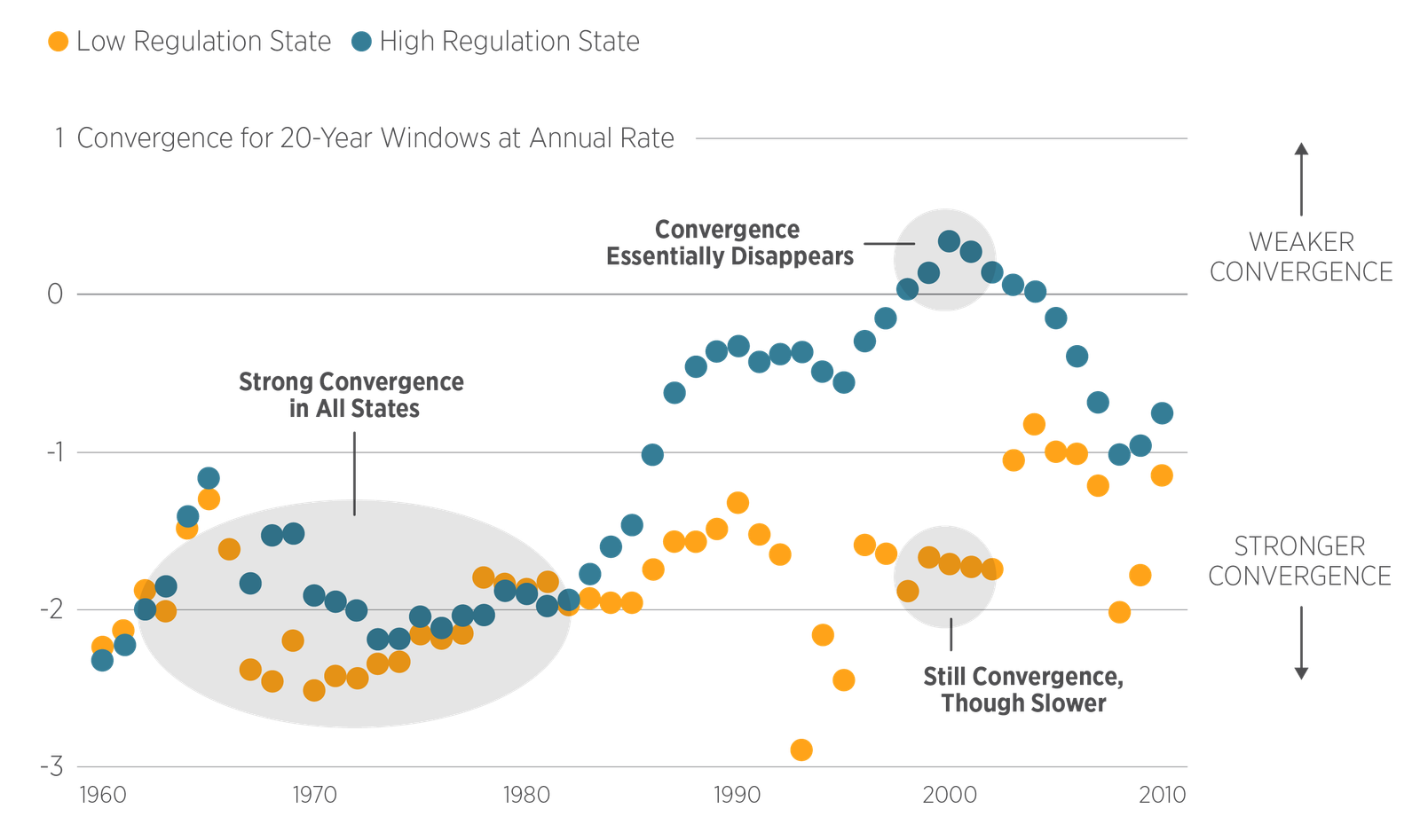

By 1990–2010, the slope is much flatter. Convergence slowed to less than half its historical pace, signaling a breakdown in the century-old pattern.

By 1980–2000, the picture changed. Low-regulation states still converged, while high-regulation states showed almost no catch-up at all.

What explains this shift in migration patterns? The authors point to the rising cost of housing in high-income areas, particularly for low-income workers, as a key part of the story. For much of the twentieth century, states converged regardless of their regulatory environment: from 1940 to 1960, both high- and low-regulation states displayed steep negative slopes, as migration equalized incomes. But by the 1980s and 1990s, this changed. In low-regulation states, convergence continued, albeit at a slower pace. In high-regulation states, however, convergence nearly disappeared.

When housing supply is flexible, higher wages in productive states attract new residents, who push down wages and generate convergence. But when supply is constrained by land-use regulation, higher demand shows up in prices rather than in population growth. Housing costs rise, in-migration slows, and only highly educated workers can still afford to move. Over time, this erodes the very process that once narrowed regional gaps.

Figure 5 makes the point especially clear: rolling estimates show convergence persisting in low-regulation states while steadily weakening in high-regulation ones. The data and model together suggest that rising housing costs, driven by restrictive land-use policies, have transformed the geography of opportunity in the United States.